Your Poicephalus and You

Story and pictures by Vincent J. Hrovat

|

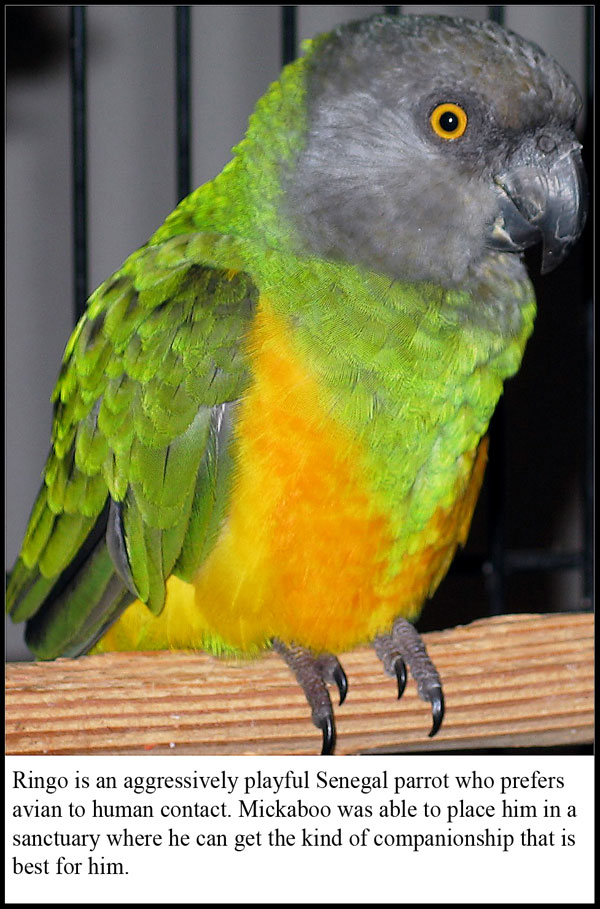

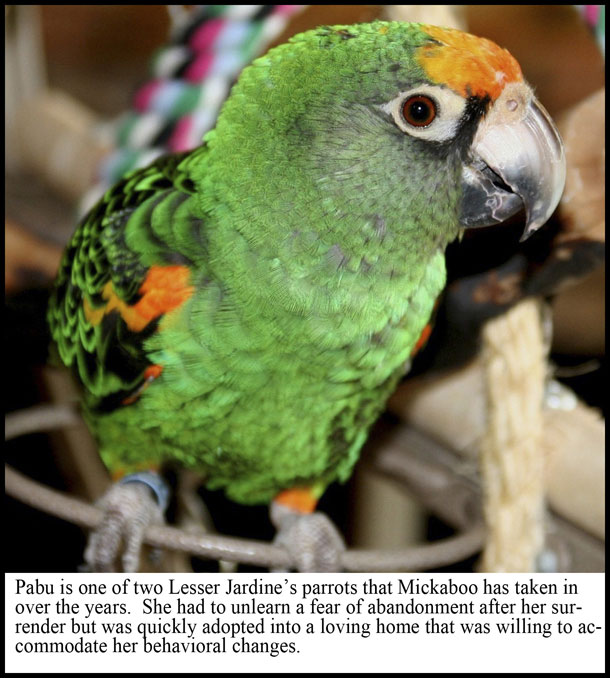

Parrots of the genus Poicephalus have quite a reputation as outstanding companion birds in the pet industry. The Senegal and Meyers parrots, in particular, are considered fairly easy, low-maintenance birds who are quiet enough to be suitable for apartment living. Some of the terms commonly used to describe these birds in aviculture include "sociable," "mischievous," "cuddly" and "fun-loving," and they are frequently categorized as great family birds.

Some people who've surrendered their Poicephalus to Mickaboo over the years have used decidedly different words to describe their birds:

- "Bites like a pit bull: once his beak is imbedded in flesh, he won't let go."

- "Will act sweet and loving, then suddenly turn vicious and inflict painful, bloody bites."

- "Screams constantly for companionship, then will attack viciously when you give it to him."

As is usually the case, the truth is somewhere between the extremes of these examples. As most behaviorists will tell you, words like "cuddly" and "vicious" are labels which can be used to describe a small part of a complex creature's behavior patterns. The Poicephalus are neither cuddly nor vicious. What they are is frequently misunderstood and, subsequently, mishandled.

The Poicephalus are a genus consisting of nine species of small to medium-sized parrots native to sub-Saharan Africa. Species of Poicephalus kept frequently as pets include the Senegal (species senegalus), Meyer's (meyeri), and Red-bellied (rufiventris) parrots, with the Cape (robustus), Jardine's (gulielmi) and Brown-headed (Cryptoxanthus) parrots seen less commonly in aviculture. The remaining three species, Rüppel's (rueppellii), Niam-Niam (crassus ), and Yellow-fronted (flavifrons ) are rarely seen in captivity and practically never as pets.

All of the Poicephalus are arboreal and eat mostly fruits, nuts and leaves in the wild. They have stocky frames, short tails, and proportionally large heads and beaks compared to most other hookbills. While the Poicephalus usually live in small flocks and congregate at feeding time, they can be extremely aggressive about protecting their personal or nesting space. The Poicephalus become sexually mature at two or three years of age, and in the next few years following that sexual maturity they can become increasingly more independent and aggressive, which catches a lot of their keepers off guard.

Many of the "vicious" Poicephalus who are surrendered to Mickaboo have recently gone through their sexual maturity and independence phase. The fact that their "cuddly" bird, which had heretofore been easy to handle, has suddenly become aggressive and even standoffish leaves people frustrated and unable to rationalize this behavioral change. They may wonder what they've done wrong to make their bird this way. Many Poicephalus owners have recently graduated from smaller, gentler birds like cockatiels so they aren't used to the more aggressive behavior and much stronger beaks of the Senegal or Meyer's parrots, who may weigh just a few grams more. Because of this, they may incorrectly categorize their birds as mean or vicious.

Perhaps the worst thing about this kind of situation is that an owner who is not prepared to handle their suddenly independent and aggressive bird can inadvertently make the bird's situation worse. In response to a Poicephalus' aggression, people may try all kinds of aggressive acts in return: yelling, spraying the bird with water, deliberately ignoring, depriving or even striking the bird. All of these are likely to make the bird's aggression worse, and will almost invariably make the bird both scared and resentful as well. This cycle can quickly and permanently damage the relationship of trust that the bird and owner have built up. To make things worse, many Poicephalus get injured when they are accidentally thrown to the floor while biting, since their tenacious beaks can be difficult to unlatch once they have a good hold. Such injuries can permanently cripple or kill a bird.

There are several techniques that can help bring an aggressive bird reasonably under control, but the bird will probably never be the same as it was before undergoing this personality change. This is a part of their growing up and we only have so much control over it. The key is to change the way that you interact with the bird to accommodate for their new mindset, while at the same time taking steps to reinforce your bond with them. Your goal is to be your bird's friend and to give him the environment that he needs to thrive in as an adult. This is not and should not be the end of your relationship with your adult Poicephalus; it's just a natural change in the continuum of that long-lasting relationship.

|

Here are a few specific techniques that will help you to work proactively with your adult Poicephalus instead of letting your relationship deteriorate:

- Exercise control! When the Poicephalus are younger you might feel safe in giving them free reign to climb over you and letting them ride on your shoulder. When they become more independent and aggressive, you need to pay much closer attention when you are working with them. Do NOT let them climb all over you anymore. Instead, you should expect the bird to step up when asked, step down when asked, stay on the playpen, etc. The best way to establish basic control is through positive reinforcement of the step-up and step-down commands. To give your bird quality, one-on-one time with you while you are doing household chores or activities, set up a small perch stand that you can keep nearby, with toys, verbal interaction and small treats to keep his interest.

- Exercise situational awareness when you do have to handle your bird! Keep your eye on him and don't let him climb around on you. If he tries to climb up your sleeve, block him with your other hand. If he persists, put him down for a few minutes, and then try again. You can greatly reduce the chance of getting bitten by paying attention!

- Teach your bird to step up and down onto a wooden stick instead of a hand. This way, a person who needs to handle him when he is scared or excited can greatly reduce the chance of getting bitten. The stick should be at least 12-14 inches long to keep the bird sufficiently far from the holder's hand. This should not be your primary way of handling the bird but you should train and reinforce with it so that your bird will not be scared of it and you can use it if needed. You do not want to alienate your bird by using the stick to create an arbitrary space between you. You DO want to minimize the chance of him biting you, for your sake and his.

- Provide enrichment: The bird should have interesting toys that keep him/her busy, even when he does not feel like interacting with you, but should not have toys that encourage mating or nesting behavior. Soft woods or papers that he/she can chew into nesting material are fine sometimes but are not a good idea for a hormonal bird. Climbing, foraging, and logic/puzzle toys are much better. Encouraging their natural arboreal foraging instinct by hanging fruits and vegetables on kabobs is a great way to keep your Poicephalus busy, but keep the selection simple - just one or two types of fruit or vegetable at a time or they may get confused.

- Take steps to minimize your bird's breeding instincts. These are the same steps that we take to help birds to stop laying eggs: remove nesting materials, provide longer and uninterrupted sleep time, rearrange cage, provide a metered diet centered on pelleted food and non-starchy vegetables, and do not pet the bird anywhere except on the head.

- Don't let your bird see a response from you. This may sound sadistic, but I am convinced from experience that some of the Poicephalus get enrichment from listening to people scream and watching them writhe. This makes these birds more likely to bite, to get that response. While you should make every reasonable effort, as described above, to avoid getting bitten in the first place, you should also maintain your composure while being bitten to reduce or eliminate this reason for aggressive behavior.

- Many Poicephalus go through what I call a "honeymoon period" when placed in a new home with a confident and experienced handler. If you know such a bird handler that your bird can go to short-term (a week or so), that handler can use this honeymoon period to partially work your bird out of his aggressive and hormonal mode and can help the bird to respond properly to basic control techniques such as step-up and step-down. It helps very much if the handler has specific experience with the Poicephalus parrots, and they have to be willing to work on behavioral modifications with the bird in your absence. Note that this is not a substitute for your working with your own bird and following all of the above guidelines! It is merely a way to help you jump-start the process.

- Don't give up! Too many of the Poicephalus that have come to Mickaboo have been locked in their cage for months or years. Never stop working with your bird and, especially, never stop being his friend.

|

About the author:

Vincent has rescued, fostered and rehabilitated several Poicpephalus parrots on his own and through Mickaboo over the past 15 years. He is currently fostering Aggie and Grover the Senegal parrots. You can see more pictures of his current and previous fosters at http://www.flickr.com/photos/eastbayvinny/sets/72157623530575534/ .